Discover our wines' history

Our History, a common vision : Persevere and Innovate.

Marie Maria embodies our unwavering strive to honor our predecessors’ heritage all whilst integrating innovations that respect our environment. We stay determined to reveal the nuances of our terroir through durable and innovative practices, thus guaranteeing that each bottle tells a tale of passion and excellence.

The wines of Madiran, appreciated for their robustness, and the Pacherenc du Vic-Bilh, known for their delicacy, are the fruit of a winemaking tradition that goes back far beyond the Middle Ages.

The cultivation of vines in Madiran is traced back to the arrival of the first wild vines in the Pyrénées around 800 BCE. However, it wasn’t until the 11th Century, with the installation of Benedictine monks and the creation of the Sainte Marie monastery in Madiran in 1030, that winemaking began to structure itself in the region. The commercialization of wine grew in the 15th century, notably around the Pyrénées.

Madiran and Pacherenc du Vic-Bilh, from antiquity to the present

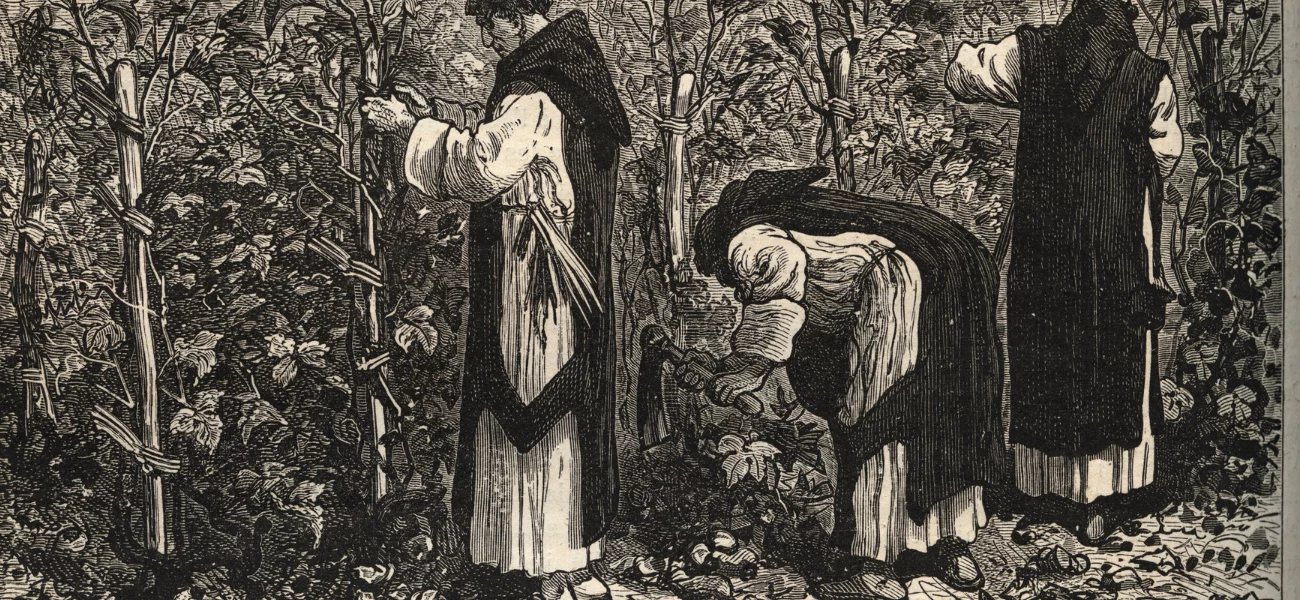

Madiran’s wines, greatly appreciated for their robustness, and the Pacherenc du Vic-Bilh, known for their delicacy, are the fruit of a winemaking tradition that goes back far beyond the Middle Ages. Our vineyard was shaped by generations, beginning with the Benedictine monks in the 11th century, who played a crucial role in developing winemaking in the region.

A symbolic identity of our history

Or logo is composed of 3 strong symbolic elements :

Our logo is composed of three strong symbolic elements:

• The stylized Sainte-Marie Church pays tribute to our geographic and historical roots.

• The shell represents the pilgrims of Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle who tasted Madiran wines on their journey.

• Finally, the star, an allegory of humanity, watches over our wines through time.

Antiquity and the Gallo-Roman Origins

Since the 5th century, the writings of Salvien, a monk from the Lérins Abbey, highlight the vibrant presence of wine in Gascony. Salvien describes a region where "the whole country is covered with vines," underlining a winemaking tradition that predates even the foundation of our vineyard. The mosaics of this period, like the one in Taron, visible in the Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, illustrate this richness with vegetative patterns that depict the vine.

In the 11th century, the arrival of monks from the Marcilhac-sur-Célé Abbey in Madiran marked a turning point. They expanded vine cultivation, making Madiran's wines popular far beyond local borders. These wines became a central element of Mass in multiple dioceses and were affectionately nicknamed "priest wines." Their reputation grew among pilgrims traveling to Santiago de Compostela, making Madiran a staple along their route.

The vineyard passed through the hands of multiple owners, including the Jesuits of Toulouse in the 17th century, and survived numerous crises, notably the phylloxera epidemic. In the early 20th century, the official boundaries of the Madiran terroir were established, consolidating its reputation.

Phylloxera nearly destroyed the vineyards of Madiran at the end of the 19th century, but the region experienced a revival in the early 20th century with the creation of the first winemakers' syndicate in 1906 and the recognition of the Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) in 1948. Continued efforts by winemakers revitalized and expanded production, ensuring exceptional quality that honors the region's rich past.

MONUMENTS BEARING WITNESS TO OUR HISTORY

The Monks’ Heritage

THE MONKS’ HERITAGE: A PANORAMA OF WINEMAKING MONASTERIES Monasteries played a central role in the development of medieval Europe between the 9th and 10th centuries. In France, these religious establishments were particularly numerous, with around a thousand in existence, including 251 Cistercian abbeys and 412 Benedictine abbeys. This dense network

The Madiran church

The Sainte Marie de Madiran church : an ancient and sacred historical treasure Both sacred and secular history intertwine in the thousand-year old stones that make up the Sainte Marie de Madiran church, a jewel of the religious heritage nested in the Gers department. Being a record of a far-away

The Madiran Priory

The Madiran Priory :A historical jewel in the heart of the Marie Maria Vineyard Within the rich historical heritage of the Marie Maria vineyard is located an unknown treasure : the Madiran priory. This building, imbued with centuries of history, finds its roots in a distant era, around 1088, when